Comments due by Dec. 11, 2015

November's solid jobs report gave the Fed a final piece of evidence, clearing the way for a December rate hike, but now the question is how fast can it raise rates given weakness in some other economic data.The economy added 211,000 nonfarm payrolls in November, and the unemployment rate was unchanged at 5 percent. Wage growth was up 0.2 percent, as expected, and October jobs were revised up to 298,000.

"The Fed goes in December, but the path is shallow, and you couldn't ask for anything more," said John Canally, strategist and economist at LPL Financial. The next clues on the pace of hiking will come from the Fed itself, when it releases its interest rate forecasts with the rate news, following its meeting on Dec. 16.

"The 12-month average job gain after this report is 220,000. The Fed's number for what keeps the unemployment rate steady is in the low 100,000s. They have to get going, but they probably don't have to get going as fast as they thought in September. It's not as shallow as the market thought. It's somewhere in the middle," Canally said.

The Fed is forecasting a 1.4 percent Fed funds rate for 2016. "The path is still going to be gradual and low. Most people believe 3(in 2016). They get to 1 percent and stop," said John Briggs, head of strategy at RBS.

Treasury yields initially moved higher and stocks gained after the jobs report, but news that OPEC was leaving its pricing policy unchanged sent oil sharply lower. That temporarily dampened the stock market rally, and the dollar gave back some of its early gains, while the euro crept higher. Stocks were up more than 1 percent in late morning trading.

Markets have been pricing in roughly 75 percent odds that the Fed will hike rates on Dec. 16, but the real debate has been what happens after that. "There's nothing standing in their way," said Jim Caron, fixed income portfolio manager with Morgan Stanley Investment Management. "Aside from an unforeseen geopolitical event, there's nothing standing in their way."

Caron said the Fed will be slow to hike, and that's in part because inflation at about 1.3 percent, is still well below the Fed's 2 percent target. He expects two hikes in 2016, after the initial increase in December.

"I still think it's going to be a slow pace. The Fed needs to resist the temptation to hike too soon. We're still at core PCE of 1.3 percent," he said. "When you're below target inflation, I still think you need to be very, very slow. Let's let these inflation pressures build up. We still are probably going to be off to the races on a slow start, or slow pace of hikes."

Caron said the strength in job growth and the positive internals of the report would be a good sign for wage growth — an important element for higher inflation.

"We might be at that juncture right now of people coming back to the labor force, the average hourly earnings looking solid, and the participation rate is looking up," he said. "I hate to sound overly optimistic. You can't make too much of a trend out of this. If this gets extrapolated into the future, this is a very good sign. It's a healthy sign that the labor market is starting to get back on its right foot. If that's the case, I don't think it's going to be too long before wages follow, and that's what we need to see."

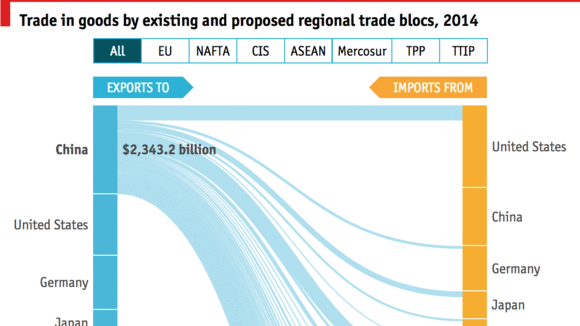

One concern for the Fed has been the strong dollar, which keeps inflation low by pressuring on commodities prices. It also hurts U.S. exports. While the jobs report showed strength in the domestic economy, the U.S. trade deficit, reported at the same time Friday, unexpectedly widened to $43.9 billion in October, as exports hit a three-year low.

Economists immediately moved to cut back GDP forecasts. Barclays said the trade deficit reduced its Q3 GDP tracking estimate to 1.8 percent, from 2 percent, and it trimmed fourth quarter growth by 0.1 percent to 2 percent.

Traders globally have been waging bets on Fed rate hikes by bidding up the dollar. At the same time, they have been shorting other currencies where other central banks are easing, particularly so the euro.

That long dollar, short euro trade went very badly for some investors Thursday, when the ECB surprised with a less aggressive than expected easing package. Markets reacted sharply — the dollar swooned, the euro jumped 3 percent and bond yields rose. The euro held most of those gains Friday.

"This (jobs report) is pretty muscular. This will keep the Fed on track for December 16 liftoff," said Ward McCarthy, chief financial economist at Jefferies.