Workers’ share of national income

Labour pains

All around the world, labour is losing out to capital

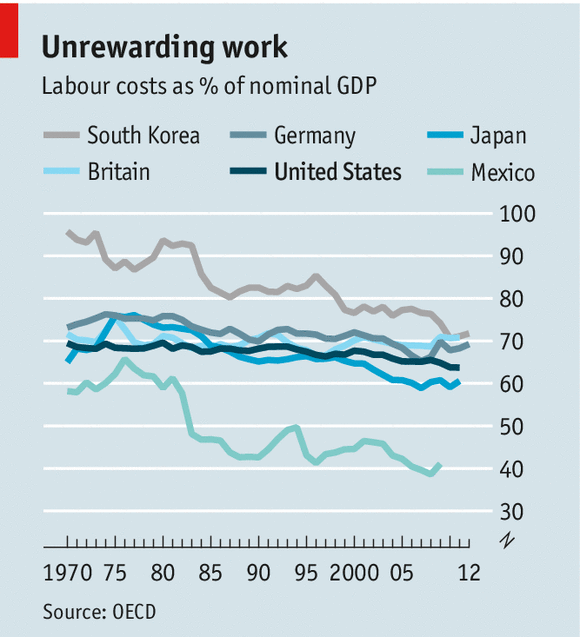

The “labour share” of national income has been falling across much of the world since the 1980s (see chart). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a club of mostly rich countries, reckons that labour captured just 62% of all income in the 2000s, down from over 66% in the early 1990s. That sort of decline is not supposed to happen. For decades economists treated the shares of income flowing to labour and capital as fixed (apart from short-run wiggles due to business cycles). When Nicholas Kaldor set out six “stylised facts” about economic growth in 1957, the roughly constant share of income flowing to labour made the list. Many in the profession now wonder whether it still belongs there.

Workers in America tend to blame cheap labour in poorer places for this trend. They are broadly right to do so, according to new research by Michael Elsby of the University of Edinburgh, Bart Hobijn of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and Aysegul Sahin of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. They calculated how much different industries in America are exposed to competition from imports, and compared the results with the decline in the labour share in each industry. A greater reliance on imports, they found, is associated with a bigger decline in labour’s take. Of the 3.9 percentage-point fall in the labour share in America over the past 25 years, 3.3 percentage points can be pinned on the likes of Foxconn.

Yet trade cannot account for all labour’s woes in America or elsewhere. Workers in many developing countries, from China to Mexico, have also struggled to seize the benefits of growth over the past two decades. The likeliest culprit is technology, which, the OECD estimates, accounts for roughly 80% of the drop in the labour share among its members. Foxconn, for example, is looking for something different in its new employees: circuitry. The firm says it will add 1m robots to its factories next year.

Cheaper and more powerful equipment, in robotics and computing, has allowed firms to automate an ever larger array of tasks. New research by Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman of the University of Chicago illustrates the point. They reckon that the cost of investment goods, relative to consumption goods, has dropped 25% over the past 35 years. That made it attractive for firms to swap labour for software whenever possible, which has contributed to a decline in the labour share of five percentage points. In places and industries where the cost of investment goods fell by more, the drop in the labour share was correspondingly larger.

Other work reinforces their conclusion. Despite their emphasis on trade, Messrs Elsby and Hobijn and Ms Sahin note that American labour productivity grew faster than worker compensation in the 1980s and 1990s, before the period of the most rapid growth in imports. Studies looking at the increasing inequality among workers tell a similar story. In recent decades jobs requiring middling skills have declined sharply as a share of total employment, while employment in high- and low-skill occupations has increased. Work by David Autor of MIT, David Dorn of the Centre for Monetary and Financial Studies and Gordon Hanson of the University of California, San Diego, shows that computerisation and automation laid waste mid-level jobs in the 1990s. Trade, by contrast, only became an important cause of the growing disparity in wages in the 2000s.

Trade and technology’s toll on wages has in some cases been abetted by changes in employment laws. In the late 1970s European workers enjoyed high labour shares thanks to stiff labour-market regulation. The labour share topped 75% in Spain and 80% in France. When labour- and product-market liberalisation swept Europe in the early 1980s—motivated in part by stubbornly high unemployment—labour shares tumbled. Privatisation has further weakened labour’s hold.

Such trends may tempt governments to adopt new protections for workers as a means to support the labour share. Yet regulation might instead lead to more unemployment, or to an even faster shift to automation. Trade’s impact could become more benign in future as emerging-market wages rise, but that too could simply hasten automation, as at Foxconn.

Accelerating technological change and rising productivity create the potential for rapid improvements in living standards. Yet if the resulting income gains prove elusive to wage and salary workers, that promise may not be realised.

6 comments:

I find it pretty alarming the way technology and trade has the potential to affect the labor share of income. Companies are always trying to become more efficient so they can outclass their competitors; therefore, it only makes sense that they are moving towards automation. However, this poses a huge problem for the factory workers that make up a significant part of the labor force. More and more of them will lose their jobs to machinery. It is difficult to imagine the implications that this will have on our economy. These people will probably have to resort to lower end jobs because their skilled labor will no longer be required. I think this has the potential to lower the standard of living for a large group of people. I’ve heard a lot of hearsay that the middle class may possibly disappear and it is this type of information that actually has me worried about it. The wealthy continue to grow wealthier because the money they save from automation is greater than the amount they save when they hire more employees. The employees that lose their jobs suffer and may end up earning less money than before; possibly even knocking them down a class on the hierarchy of wealth. Another significant threat is trade because instead of producing our own resources, we buy them from other countries that produce them more efficiently because it is less costly. This lowers the amount of available jobs in our domestic country. Outsourcing is also another way we lower the amount of jobs and potential for labor share income growth. While the consumer may appreciate a cheaper and more efficiently produced product, I doubt the workers are okay with being replaced by machinery. Like the article mentions, we have to consider if the benefits from efficiency outweigh the costs of lost jobs or lower wages. I just hope that companies understand that there should be a limit to how much they downsize in the interest of profitability. By pursuing profits and laying off workers, they are having a profound effect on our economy. Personally, I find it frightening that businesses are moving towards more computerized processes. I also don’t think that it’s unfeasible that we will one day see entire businesses that are nearly fully automatized. We can only hope that companies will value their workers enough to not let this happen, but with competition today, this seems unlikely.

-Anthony Riccio

The main point of this article is that the labour share of the national income has been falling across much of the world since the 1980s. In the same time period, the top 1% of workers have experienced increased benefits due to growth. All these changes could be attributed to changes in technology which have increased productivity and change in employment laws. Of course, as technology improves and increases productivity, workers make less money while top 1% workers reap the benefits of increased profitability. While this change in events is logical and easy to follow, it is an unfortunate side effect that workers suffer and experience decreased labor share of income. Technology is not the only factor which cuts the number of jobs available for labour workers. Outsourcing to other countries where the fixed and variable costs of production are cheaper also takes jobs away from workers here in the United States. As all these changes take place, more and more American workers become unemployed while business people making decisions such as implementing new technologies or outsourcing or regulating business policies are reaping the benefits. It is an uneven earnings process. There seems little chance that this will change moving forward seeing as business will always try to cut marginal costs to become more and more efficient and maximize their profits.

-Kaitlyn Szilagyi

With the technological advancements we have today, it only makes sense to upgrade and replace physical labor with machines. It is less costly and produces a better income and production rate. The owners and CEO's would be greatly compensated for their trade off however with their positives brings a strong negative impact to the individuals who made being employed by these owners a lifestyle. The labor work rate has declined recently due to trade and technology. The idea of swapping labor for software is a well known idea which is spread through companies everywhere. Why? Because it saves money. However on the other hand, a vast amount of people are being put out of a job. This in fact may have an effect on the middle class's way of life. Since the addition of tech to companies, high and low skilled jobs increased. This means those who live a middle class life and work the middle skilled jobs which were replaced by machines must find a way to maintain and afford their capital lifestyle. Can you blame the owners for putting others out of a job? Quite selfish but personally no I cannot. The rich have the power to remain and even become richer and that fact does not look to change anytime soon.

-Mitchell Borrero

What this article is speaking to is the continuing trend in America as well as in other countries in which the top 1% of the population continues to control more and more of the wealth and money. As companies and corporations remain looking for better ways to be more productive, it seems as if we are not focusing on the needs of the true labor force of our country. More and more workers are being replaced by machines due to the fact that they could do much more work in short periods of time and over the long run they are cheaper seeing that you don't have to pay a machine a hourly salary. Overall, advances in technology are making the way we could produce goods much more efficient and thats what many modern companies are looking for. Although I would like this problem to be solved I don't think it will be. Competition is the driving force behind the decisions that a company makes and if they don't keep up efficient means of production they could fall behind their competition. It seems as if these workers losing their jobs might have to just look at other jobs that will most likely yield them less income. While this seems very unfortunate, with our developing world and constant pressures of competition put on businesses to survive in this tough economy, it may be a problem with no fair solution.

-Michael Scalia

It didnt come at surprise to me when i read the effects of technology on labor. It is understandable that companies are always looking forward to acquire the latest technology in their production. They always want to be more efficient than their competitors and this results in factors workers being laid off. The reason why the share of income of the top %1 didnt decrease is because they are not on the field workers who have to work with machines. They are mostly CEO's and directors who decide to lay off the on the field workers to decrease costs. I think the government should intervene in order to keep the labor force alive. It should be the governments responsibility to create jobs for laid off workers instead of providing them welfare and giving them an incentive to be lazy.

-Asfand Khan

As you can see, the top 1% of the American population continues to control the money in the country. Its like this all other countries too, not just America. Workers jobs are being taken over by machines. Machines are capable of doing work more efficiently and are also a cheaper way to run your business. The workers are losing their jobs and their doesn't seem to be a solution to that. Competition is fierce and businesses just won't the best way to manufacture goods quickly and with high quality. There is so much new technology that human workers aren't as useful anymore. This is just a problem that our economy is going to have to deal with for the seeing future.

-Danny Prisciotta

Post a Comment